Join us as we chat with Tara Finn about her journey recovering from an eating disorder, with a background of ASD, ADHD and OCD.

She also shares her experience navigating other conditions such as gastroparesis and epilepsy that developed as a result of her eating disorder.

Meet Tara!

Tara’s Recovery Journey

Living with ARFID and OCD

Recovering From Anorexia

Recovering From An Eating Disorder With ASD And ADHD

Maintaining Recovery

Creating A Fulfilling Life After Recovery

Living With Health Complications From An Eating Disorder

Don’t Settle For Halfway

Meet Tara!

I’m studying a Bachelor of Nutrition and Dietetics, and I have a history of having eating disorders pretty much my whole life. I am also neurodivergent and have struggled with mental health for most of my life.

I’m very passionate about helping people and hopefully being able to help more people.

What’s one thing most people don’t know about you?

I know I’m studying dietetics, but I was such an English girl in year 11 and 12. I didn’t know math or study science.

It’s been really humbling having to learn math and science at uni. It’s very unexpected because now I’m doing a very science-heavy degree. But before I ended up here, I wanted to be an English teacher.

View this post on Instagram

Tara’s Recovery Journey

I’ll take things way back – I basically came out of the womb with mental health problems.

I’ve been in therapy since I was around six, and back then, it was just referred to as ‘food anxiety’. I’d never really heard the term ARFID until I was a teenager, but at this time it seemed like a food anxiety/selective eating disorder kind of thing.

I was always a very anxious kid. I had lots of sadness at a very young age, so I was always in therapy because of this.

Living with ARFID, it was very misunderstood. People always told my parents, like, “Oh, she’ll grow out of it. It’s just picky eating.” And they would say, “Leave her at the table until she finishes,” and I would sit there all night.

I always liked the food I ate. I didn’t eat a big, diverse range, but I loved the food I did eat.

Then when I was about 14, I went overseas. My family’s Irish, so we went to Ireland for a little bit, and then we went around Europe. It was good fun. I remember I would be in Italy eating plain pasta and plain pizza bases. I was eating a good amount, but my diversity wasn’t there.

When I was in Europe, though I always had anxiety, it started to really take over. I’d never been on a trip that long. We went to a lot of places, and it was very overwhelming for me, and I think I was just never the same.

Being Diagnosed With OCD And An Eating Disorder

When I came back, I was diagnosed with OCD. Looking back on it, I always had OCD. I always struggled with obsessions and compulsions. But, I remember this trip really started a lot of it for me.

I was put on medication, and I was put in therapy. It was very misunderstood because people have this concept of OCD, and it’s not exactly what I experienced.

I started to struggle with food a little bit. It was accidentally, not on purpose, and lost a little bit of weight. I remember my psychologist said to me, “Oh, you look like you’ve lost a bit of weight.” And it just flipped this thing in my brain that just turned into this hyperfixation.

Then I went on a holiday when I was 16, and I came back, and everything just went downhill very quickly. I fell into behaviors and really struggled, and I was diagnosed with anorexia. It was like this weird blend of ARFID and anorexia, and they didn’t know how to treat it.

It was very confusing for everyone, and very confusing for myself.

I was admitted to hospital just after my 17th birthday, and pretty much was in and out of hospitals for quite a few years.

I haven’t been in hospital for a couple of years now. I’ve come very far. I am very grateful. I had lots of things happen over the years, and being in treatment with a neurodivergent brain and ARFID, and being treated for anorexia is very hard.

I’m still living with ARFID, but I don’t struggle with anorexia at all. I’m much better, thankfully, but it took a lot to get me here.

Living with ARFID and OCD

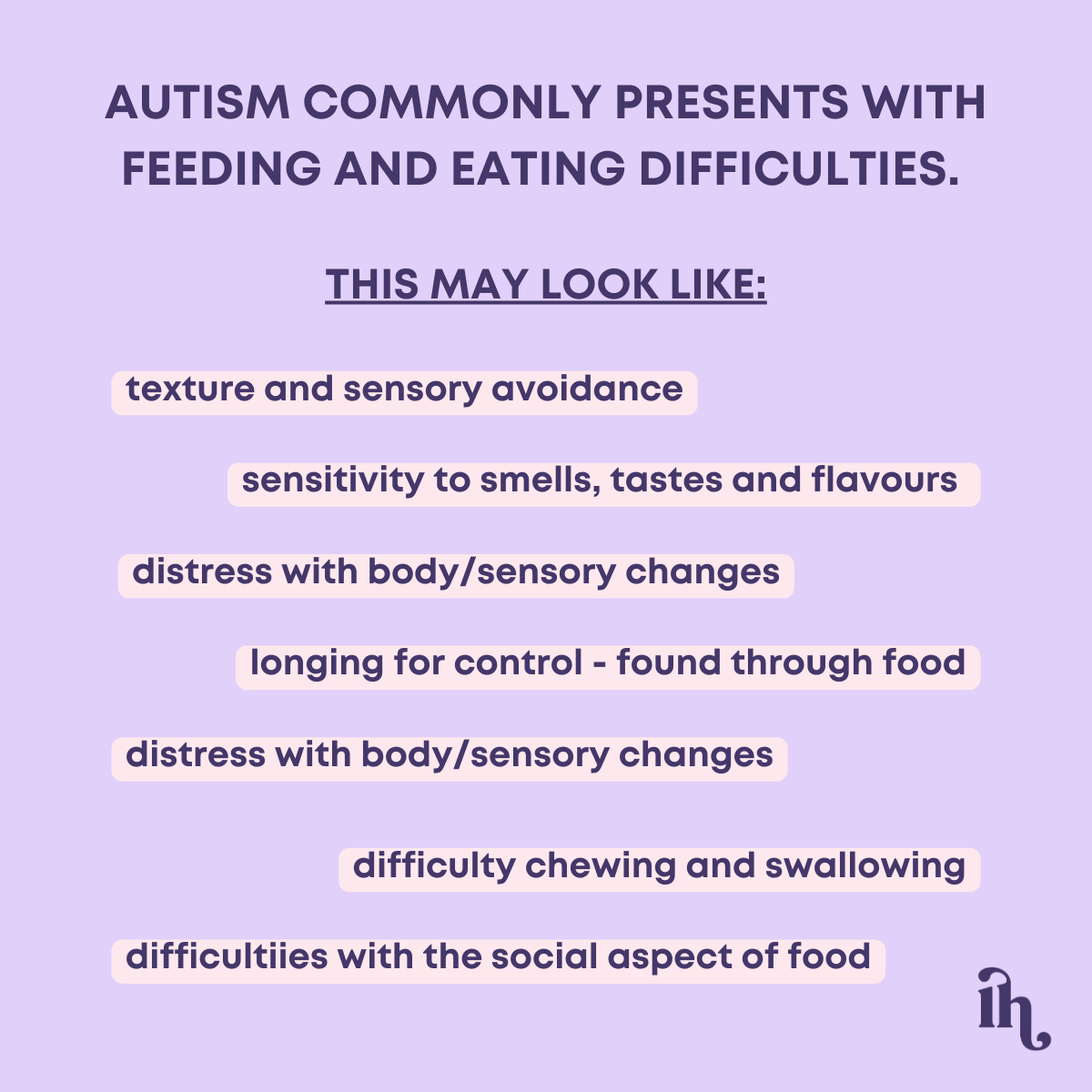

ARFID stands for Avoidant Restrictive Food Intake Disorder.

Essentially, there’s a few different types, but commonly it stems from a fear of say, if somebody has a traumatic incident where they choke – they develop a fear of eating because they associate food with that negative experience. There can also just be a disinterest in food.

For me, it was very related to sensory texture and smell. The way I describe it is, when I would eat something that I didn’t feel comfortable eating, not like a restrictive sense, it sounds weird, but it would turn to jelly in my mouth, and I couldn’t deal with the texture.

It was really overwhelming. For me, it was built into being autistic, and like having all the sensory difficulties, and food was just such a source of anxiety for me.

It’s really hard to navigate conventional eating treatment where they don’t take into account that kind of condition.

Tara’s Experience With OCD

Moving onto OCD. OCD is Obsessive Compulsive Disorder. Typically when people think of OCD, they think, “Oh, you love washing and all that kind of stuff.” It does present like that for a lot of people, and that is equally as challenging. But for me, it’s like extreme obsessions and then compulsions to manage the obsessions.

So it’s like, I’ll get a thought. If I watch something that’s disturbing or I hear something, it gets stuck in my brain. Like, I always say, like gum in hair. You know, when you get gum in hair and it’s stuck? That’s how thoughts are in my brain.

For me it underpins pretty much everything, because, as well as the ARFID, for a lot of people, when you’re unwell physically and you’re weight suppressed, your anxiety and people’s OCD and depression worsen.

For me, it was the opposite. Because when you’re unwell, my brain was literally incapable of thinking of anything else other than food and weight and all that kind of disordered stuff. So my OCD kind of fell to the back burner.

Once I realised that, it really fuelled my eating disorder – the anorexia side of it. It made recovering from an eating disorder really complicated.

I found weight restoring so hard because it meant that I was voluntarily going into the experience of my OCD flaring up. My OCD makes me very detached from truth and reality, where I’m fully convinced that all these things are going to happen.

For me, it was the main reason I didn’t want to get better from anorexia. I still live with it on a daily basis, but I’m very well managed on medication, and I don’t have any desire to use restricting and eating behaviors to cope with that.

Recovering From Anorexia

When I went into the hospital for the first time, I didn’t know anyone with an eating disorder or recovering from an eating disorder. I was not on any social media groups, and I didn’t have any friends with similar experiences.

I just went into it very blind, I didn’t know anything. Then I met all these people and I kind of fell into this world. My world became so small. I lost so many friends, I isolated myself from everyone, I stopped going to school… It seemed like I kind of fell off the face of the planet for a lot of people.

I just kept cycling in and out of different hospitals, and developed a lot of health problems as a result. They weren’t my turning point for recovery, though. A lot of people expected that the damage I had done would be the point where I decided to get better, but it’s not that simple.

Reaching The Turning Point

My biggest turning point was in my last admission for anorexia. I was in the hospital, and my one-to-one nurses were girls I knew from school. They were my age, and they were working in the hospital and looking after me.

It hit me hard. I thought, “What am I doing?” It wasn’t a light bulb moment, but it was significant. I realised that I didn’t know what I was doing anymore. Looking back, I’ve realised that anorexia was a way of coping with not wanting to grow up.

When I got sick and first started having behaviors, I was 15 or 16. We were being told at school to pick our subjects and decide what we wanted to do at university. All my friends were doing teenage things, being normal teenagers, and I wasn’t ready.

The eating disorder worked to stop me from having to grow up. Now, in my head, I’m still 16. My friends are all turning 20 or 21 this year, and I’m turning 22, but I still feel like a teenager. It’s hard to describe.

I was in the hospital for years, and after that turning point, I was just so traumatised from all my experiences. Hospital can be an amazing thing for a lot of people, but navigating it with the comorbid conditions I had was really tough.

The Importance Of Finding The Right Support

My mom found a woman who specialises in ASD and eating disorders. She used to run the Bronte Centre, which is now the Door Two Foundation. Her name is Jan, and she’s incredible. She literally saved my life. I can’t describe how affirming she was.

She’d been through similar experiences with her daughter, and she cared for me so much. When I got discharged from one of my last admissions, she drove from Melbourne to Sydney to help us. She was just incredible. Finding her was a big turning point.

I started to build a life outside of my eating disorder that I wanted to get better for. I began making choices every day in that direction. It was uncomfortable and painful, and it was the hardest thing I’ve ever gone through.

You spend so long with these cognitions deeply entrenched, and then suddenly, it feels so foreign to change.

But, I’m very lucky. I have an amazing family who helped me a lot, and I’ve always had really great outpatient treatment. It’s been a journey over the last few years. I’ve been fully better for a year or two now, not engaging in any behaviors for over a year, probably two years now, since I moved out of home.

Surrounding myself with people who have good relationships with food has been very helpful.

Recovering From An Eating Disorder With ASD & ADHD

I grew up with people making comments like, “Oh, you’re probably on the spectrum,” and it was often used as an insult. Because of that, I had these preconceived stereotypes in my brain.

During one of my hospital admissions, they told me I should get an assessment for ASD. I feel really sad about this now, but I was really offended at first. It feels really wrong being offended, but it was the way society viewed things back then. I was 17 or 18, and autism wasn’t as well understood as it is now.

Having a diagnosis is a privilege because it’s so hard and expensive to get one. I was very lucky to have an assessment.

I was only diagnosed with ADHD last year. My whole family has ADHD, except for my mum—they were all diagnosed as kids. I think I masked it very well and did well in school, so I didn’t fit into the traditional preconceived notions of ADHD.

The ASD has really influenced my experience. I don’t think I would have developed ARFID if I didn’t have ASD.

Navigating treatment with an autistic brain was very challenging. I couldn’t deal with changes in routines, textures were overwhelming, and everything was so overstimulating. It was hard to navigate my relationship with food and my body because I felt so uncomfortable all the time.

Being Diagnosed With ADHD

The ADHD made things more complicated—I would lose my appetite, forget to eat, and prioritise other things. It was very up and down.

I think if I had access to an autism assessment earlier and been diagnosed earlier, treatment would have been very different. Until they had the assessment and figured it out, they didn’t really know why I was engaging in these behaviors.

Now, I understand, and everyone else understands too. I’m much more open about it with people in my life. My relationship with myself has definitely improved. When I first got diagnosed, I didn’t tell anyone. I didn’t tell any of my friends. A year after we moved in together, I told my best friend, and he said, “I know.” I was like, “Okay, you’re my best friend, I’ll let you say that.”

It’s definitely gotten better. With food, recovery was hard because I was so set in my ways and routines. I had these boxes in my brain, which is the only way I can describe it. If something didn’t fit into a box, it wasn’t allowed.

Now, I’m more aware of myself. I know how to keep myself safe and protected. I also have a lot of care that is very affirming to my being autistic.

The Importance Of Finding The Right Care During Treatment

When I was recovering from an eating disorder, everything was basically labelled as just depression and anxiety, but with weird behaviors they didn’t understand. Once I had the diagnosis, my assessor wrote a detailed document about my specific challenges and how to overcome them.

I work with a psychologist I’ve seen since I was 15. She has been through everything with me, and she has the document. She knows exactly how to help me deal with things. We work on changes, altering my routine, and dealing with overwhelming emotions, feelings, and senses.

We also work on putting myself in environments that I find really overstimulating.

In the hospital, they were able to understand more about how to care for me and why I was engaging in certain behaviors. They also understood why I was so resistant to getting better because food had become a hyperfixation for me.

Maintaining Recovery

I consider myself very fortunate to have such strong supports.

Dealing with the health issues that arose from my eating disorder has been challenging, but my family has been incredible. I would do anything for them, and they reciprocate without hesitation.

I call my mum at least four times a day, and she’s always there for me. Throughout everything, they never gave up on me, and I feel incredibly supported by them. It’s a debt I feel I owe to myself as much as to them.

I’ve built a life that I always believed was worth recovering from an eating disorder for. When I was in hospital, I couldn’t envision the life I have now—living independently, studying, and working. This life is something I cherish deeply, and I have no desire to revert to the behaviors that once dominated me.

I’ve reached a point in recovering from an eating disorder where I’m fully committed; there’s no looking back. Someone once advised me during my hospitalisation to give recovery a dedicated timeframe—six months or a year—and if I didn’t like it, I could return to my old ways.

However, I realised that nobody recovers and regrets it. This mindset carried me through, and after a year, I found happiness and contentment in my new life.

Creating A Fulfilling Life After Recovery

When I was struggling with recovering from an eating disorder, I felt like my world was so stagnant and small—I didn’t find joy in anything. Waking up each day was a struggle, engaging in harmful behaviors felt like a prison, and the constant fear of hospitalisation was traumatic.

During COVID, it exacerbated everything. I spent six months in a hospital without seeing my siblings once, surrounded by others who were also unwell. My whole existence revolved around being unwell.

As I slowly recovered enough to leave the hospital, my dad encouraged me to “get a life.” At first, I resisted because I didn’t see a path forward. But gradually, I began reconnecting with friends, pushing myself little by little.

Strangely, I decided I wanted a job—an unconventional move when recovering from an eating disorder, but it worked for me. I saw it as a reason to eat properly and take care of myself. Having that job became a privilege and motivation to stay well.

My dad also introduced me to yoga, which became a daily practice at the end of each day, alongside meditation with him while my mom cooked dinner. These routines started bringing me joy.

I began exploring foods I liked, building hobbies, and socializing more. I started considering what I truly wanted to study and do in life.

Gradually, these small joys began to outweigh the negatives, and created a sense of fulfilment.

Get your copy of my free 3 Steps To Stop Cravings eBook here!

Living With Health Complications From An Eating Disorder

The epilepsy diagnosis came as a complete shock to me. I had my first seizure while in hospital, just as I was starting to improve in the program. I don’t remember much except waking up surrounded by medical staff in the ICU, disoriented and scared.

The hospital initially didn’t take it seriously and didn’t perform tests. It wasn’t until I had another seizure months later that they conducted an EEG, revealing epileptiform and abnormal brainwaves. It was something I had never considered before and was bewildering.

Since starting medication, my seizures have been managed well under the care of a good doctor. They only occur when I’m physically unwell, which motivates me to prioritise my health. The fear of having another seizure is constantly on my mind, driving me to stay vigilant when recovering from an eating disorder.

Developing Gastroparesis

As for gastroparesis, it started with sporadic stomach issues that were initially dismissed as reflux. However, it escalated with symptoms like vomiting hours after eating.

Fortunately, my doctor took me seriously, and I was diagnosed with delayed gastric emptying after tests with a gastroenterologist. This condition made food a source of distress as I had to plan my day around it, limiting my social interactions and making my world feel smaller.

Despite trying various medications, managing gastroparesis has been challenging, and it sometimes causes others to doubt my recovery journey. This condition developed separately from recovering from an eating disorder. While it’s improved with treatment, it’s a reminder of the ongoing challenges I face.

I had an NJ tube inserted into my intestines, and it became a routine of getting sick and having it replaced. It was quite an ordeal, but it was incredibly helpful at the time. I’m very grateful that it’s been a year since I’ve been off it and able to eat normally again. It was a blessing during that period of recovery.

It really highlights how serious eating disorders are and their lasting effects. Dealing with things like epilepsy and gastroparesis are constantly on my mind.

Sometimes I get frustrated with myself, feeling guilty as if I caused these issues. It’s easier to extend compassion to others in similar situations than to myself.

But, I’m learning to let go of that guilt and understand that it’s not my fault. It’s reassuring to have supportive doctors managing these conditions effectively.

Don’t Settle For Halfway

I would say my key take-away message is: don’t settle for halfway.

People often talk about quasi recovery, but it’s easy to fall into the trap of feeling better than before – but not quite where you want to be, and just existing there for a while.

I want people to know that they don’t have to do that. You can push for a life where you’re free from the struggles, where life is vibrant and fulfilling.

Halfway won’t give you the richness of experiences that a full life can offer.

While I no longer live with anorexia, I do face challenges every day, but I push myself because I know halfway isn’t enough.

Life isn’t always amazing—I have bad days—but I’ve learned to manage them with healthy coping mechanisms instead of getting stuck.

Recovering from an eating disorder is possible!

Where you can find Tara:

Instagram: @fuelledwithtara

Comments +